Confessions

of an Economic Hit Man explores the

ways political and economic power have been wielded to ensure an increasing

concentration of wealth and power in a handful of countries, including the

United States. John Perkins, the

author, presents this through recollections of his own time as a so-called

‘Economic Hit Man’ or EHM. His principal

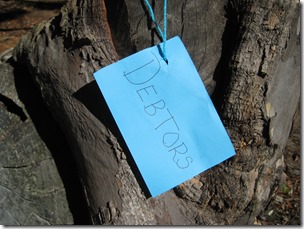

role was to convince the leaders of developing nations that the best course of

action involved significant infrastructure projects, financed by loans, and

built by U.S. engineering and construction firms. These projects ensured that development money

given these countries ultimately found its way back to the United States; the

public debt resulting from these projects insured that these countries leaders

remained compliant to North American and European political interests who could

enforce their will through the promise of aid and the possibility of loan

forgiveness.

Perkins does not explicitly make use

of a theological framework, and may even resent the effort to impose one;

however his work shares many concerns and likely even influences with South

American Liberation Theology. Perkins

focuses largely on systemic problems—he is careful to explain that even when he

was an EHM, he was not part of some vast conspiracy, but rather in a position

to see more explicitly the result of broad structures and systems. Additionally, he spent some time living with

indigenous peoples in Ecuador, and developed a relationship with Omar Torrijos

of Panama. These experiences may not

have a direct relationship to liberation theology, but at the very least show

that he was steeped in a common history.

Perkins also makes little explicit

mention of Africa, however the systems he draws attention to through accounts

of his work in South America and Asia operate throughout the world and are

relevant to all people, especially those working in development or concerned

about global poverty. CWS Africa is

aware of many of these issues, and focuses on sustainability and building community

resilience and capacity, rather than seeking to sell North Atlantic models of

living. This book complements work there

by providing an explicit framework for what CWS is trying to not do.

This text challenges readers,

particularly those from the United States and Western Europe to examine

carefully their beliefs about how aid and development work and who aid and

development projects really serve; it also challenges people to consider their

place in the global economic system. As

Perkins notes, there is no shadowy conspiracy pushing this agenda, rather it is

the result of deep set assumptions and structures. The individuals who sustain these structures

generally have little to no idea what they are doing, and many are even acting

with highly altruistic intentions, but because of a lack of critical

examination, those intentions do not lead to beneficial results. This has reinforced my awareness of the need

for careful consideration and extensive consultation with beneficiary

communities before undertaking any development project to insure that they are

really the ones benefitting the most, and also to deeply examine the

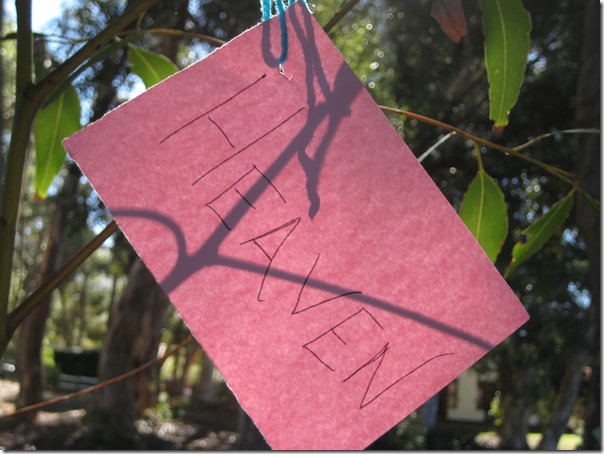

repercussions of my own daily purchasing decisions. This book issues a clarion call to the Church

and church leaders to work to break down these structures as a necessary

precursor to the coming of the Kingdom.

I actually gave this book to every

member of my immediate family for Christmas this past year, but most, if not

all people would benefit from reading it; these structures are so deeply set in

our consciousness that without regular and constant reminders, they may very

quickly disappear from consciousness.